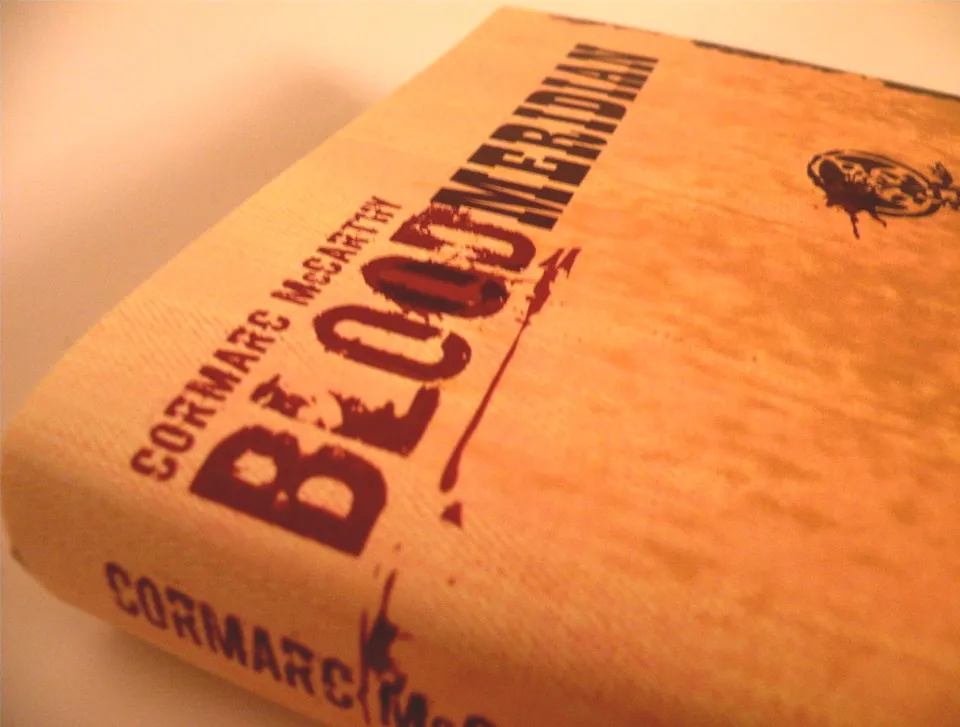

Blood Meridian by Cormac Mccarthy is one of the most notorious examples of a book that has faced challenges in being adapted into film. Its dense and rich subtext paired with its austere violence, while expressed beautifully and poetically through Mccarthy’s prose, has proven more than difficult to translate to the silver screen. Though many prominent figures have tried, it seems to be considered all but doomed for failure. On its face Cormac Mccarthy’s Blood Meridian is an obvious candidate for film adaptation. As one of the most acclaimed American authors and having two film adaptations already, it would seem astonishing that what is arguably Mccarthy’s masterpiece hasn’t been made already. However, under a more critical eye, it becomes more apparent where the challenges have been.

Blood Meridian takes place along the border between the United States and Mexico in the mid-19th century. It tells the story of “the kid”, the book’s unnamed protagonist, and his journey with a gang of scalp hunters based on the real historical “Glanton Gang”. The story itself is an unflinching, brutally violent deconstruction of the classic American western. Its hallmark violence is a significant contributing factor to its difficulty in translating to film. It is not that brutally violent movies haven’t been made or successful, but it is the sheer volume of senseless and uncaring violence that makes the story so harsh. There are no flashy stylistic flourishes, but rather blunt depictions of gruesome horror.

Brutal violence alone, however, is not enough to disqualify a book from adaptation. What makes Blood Meridian exceptionally difficult to adapt is the terseness of Mccarthy’s dialogue which manages to carry so much subtext. It would be no easy task for the director and actors to conjure the subtle implications of his words. Mccarthy’s use of precise detailing of the world from scene to scene is used as a mechanism to drive the story just as much as the characters themselves. His rhythmic prose demands the respect of any director and cinematographer who dares to capture the essence of his book.

Assuming a filmmaker can find a way to solve these challenges, there remains the obstacle of casting. While “the kid” may not pose an exceptional problem for casting, as his role serves more as an observer than a profound personality, the same cannot be said for the infamous villain, Judge Holden. Judge Holden is not your typical antagonist. Whoever were to be cast as “the Judge” would need to prove capable of exuding a cold, stoic evil; an evil that is just as matter-of-factly violent as it is charismatic and sharp-witted — less a comic book villain capable of evil, but more the very essence of evil itself.

Judge Holden is an educated man who speaks in philosophical parables about the nature of man and of war. He also stands as an embodiment of the amoral nihilism that pervaded the vicious western frontier of that time. What is often his most often quoted line: “Whatever in creation exists without my knowledge exists without my consent” stands as a succinct representation of his overall attitude towards the world.

Luckily, there are many talented actors in Hollywood, and it would not be impossible to find a capable actor, nor a capable director. In fact, as many as five attempts have been made to get this adaptation written and filmed, including attempts by industry titans such as Ridley Scott and Martin Scorsese.

And yet, even with those pillars of filmmaking, the novel remains unadapted. Technical challenges aside, what may be the biggest hurdle is a matter of logistics. The rights to the movie are owned by a single man rather than a studio. Scott Rudin, a Hollywood producer, must be on board with whatever project is proposed.

Assuming the stars aligned, and the right director was able to get approval, and was able to cast the right people, the filmmaker would have some templates to work with. This is one of the faint glimmers of hope that the adaptation has. Mccarthy has multiple works that have already been adapted, the most successful being the Coen Brothers’ No Country for Old Men. The Coens were able to capture the bare and beautiful landscapes depicted by Mccarthy. Not only was the translation of mood and scenery successful, but most notably the biggest success was casting the right antagonist. Through Javier Bardem, No Country for Old Men had its cold and enigmatic villain. It was with these tools that they managed to adapt Mccarthy’s work into an accessible film without conceding the substance of his prose.

Beyond Mccarthy’s other work, there are other films that have similar aesthetics and pacing that a potential filmmaker could take cues from. The main example that I believe fits is The Revenant. It is a movie that has a slow and methodical pace, has very little dialogue, and uses much of its time to showcase long, sweeping shots of vivid landscapes. The comparison also works because The Revenant does an effective job of communicating unspoken themes and subtext despite the very few characters and lines of dialogue, a feat that would need to be replicated for Blood Meridian.

It’s safe to say that Blood Meridian remains unadapted for understandable reasons. It is difficult enough already to get any film made, let alone a movie that would undoubtedly be so inaccessible to a general audience. While Blood Meridian has often been deemed unfilmable, it remains possible that with a stroke of luck the right crew could not only make the adaptation happen but also manage to make a compelling piece of art that does justice to its source material.

Wracking our pea brains trying to come up with an actor who would portray the Judge well, without just saying Daniel Day-Lewis…